Being me without a me

The paradox is our strength

People think that I am a “me,” but I am not. I was once listening to a podcast where the host mentioned that a question commonly asked of people—who are you?—leads most respondents to answer with their occupation. I am a geologist. I am a doctor. I am a teacher. In the silent space before the host began giving these examples of responses, I piped up to no one—“I am me!”—by which I meant I am no one at all. I blushed when I heard what I was supposed to have said.

I am entirely embarrassed sometimes to discover I am embodied. All of these efforts to shift between perspectives, to fragment into frontiers of difference, to shed being in order to truly experience it and…shit, I am stuck in this body. This body will be judged. It has been judged. Is it pretty? Thin? Sexual? Can I hide it with my brother’s hand-me-downs? Or now, how do I keep thinking and sharing ideas that were never mine to begin with from behind this aging face? Because people will see that first and decide. What they will decide won’t matter, because the overall effect will be to affirm from the outside, oh yes you are indeed a you. I see you. I name you.

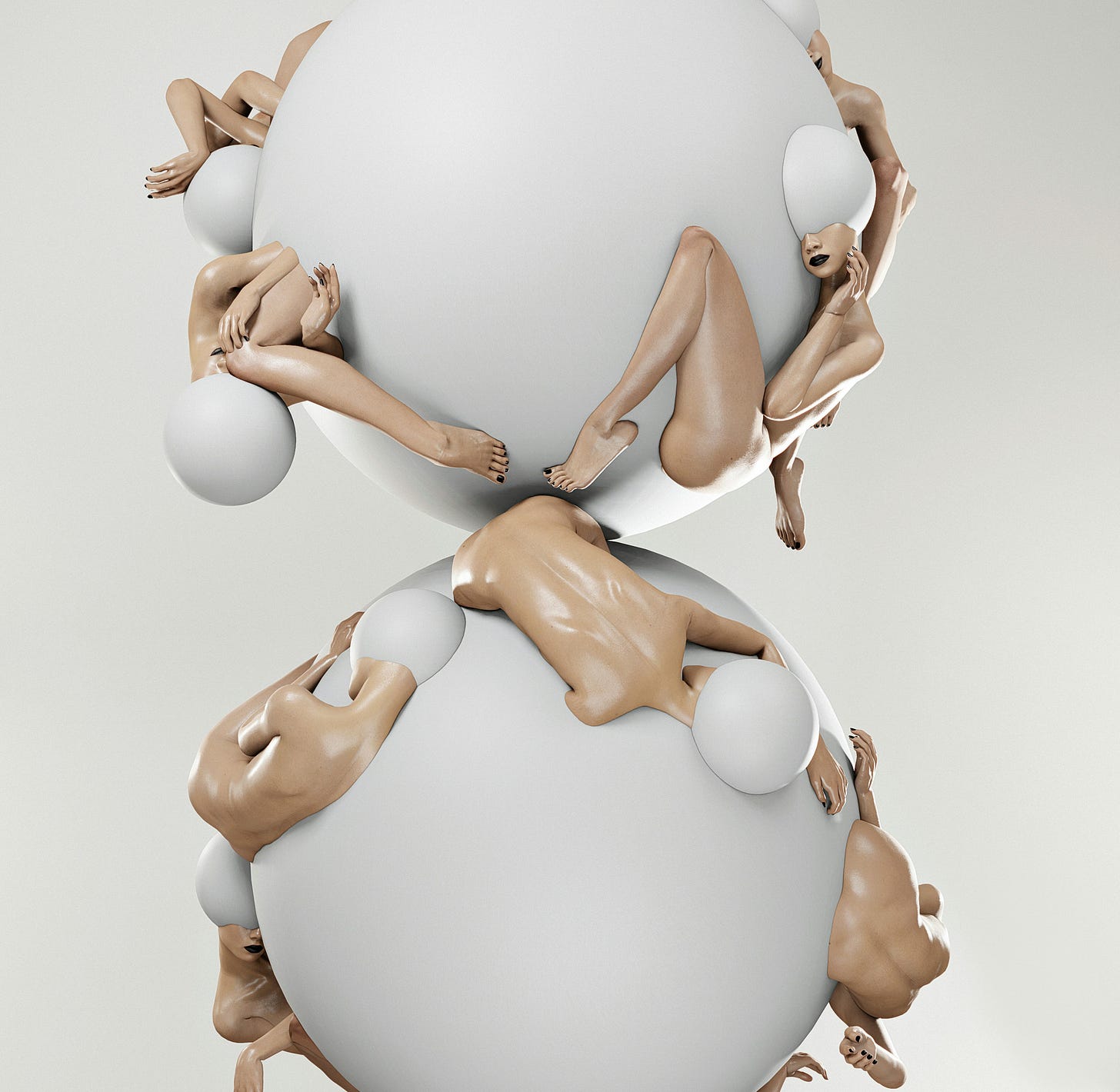

But I don’t see me. So, how can you? It is a strange paradox that I don’t expect to resolve. bell hooks once wrote that home is not a single place, but many locations, or maybe one non-location-bound place where “one confronts and accepts dispersal, fragmentation as part of the construction of a new world order that reveals more fully where we are, who we can become, an order that does not demand forgetting.” Would you like a new world order? I would if it would allow for the kind of breakage hooks describes, the kind of piecing apart of self and present that can open up an integrated becoming where you don’t have to only be a you, and me not only a me, and the past is not a futile longing but something carried carefully in all its pieces and pierced through us in order to make something bloody, but bloody beautiful. Where we don’t have to forget the obvious—that there is no possible way we all got here from nothing without being the same thing in the first place.

I can’t be here without you, you know. I can’t be me without you either, if you want to force that silly title upon me. What I want to do though is know more about you, to see what you see—as much as you will let me, the more the better, to feel your pain. If you tell me, it will help, because I already feel it—the pressing ache that has been the only real and consistent way I have defined my “self” throughout life. But it isn’t mine at all. It is yours…and yours…and also yours. I am just broken enough to have cracks where the ache can settle. I am just loose enough with space and memory and whispers to swim in the hurt and not be able to feel where I start and you begin.

I am not special. Far from it. I am not even me, remember? How could I be special? During the pandemic, when you sometimes needed to drive achingly many miles to testing locations in order to prove negativity to work or to attend school, one of those horrific outings reminded me as much. I had injured my back badly two months prior and sitting in the car driving down, I could hardly focus on anything beyond the tightened space of seizing pain. We were on our way to a site which was exclusively limited to daycare providers or attendees. My son’s home-based preschool had been shut down because of a COVID case and now they were requiring everyone to show they didn’t have the virus in order to reopen. So, we were on this excruciating excursion. The testing site was many miles away, many trucks that my son named and called out as we passed them on the highway, many minutes split into seconds—each one of which broke into a never-ending space of pain…and then contracted into me. I was pain. All else had been subtracted.

Finally, we arrived at the testing site. It was located in the otherwise empty parking lots of a mall with stores where nobody was shopping anymore. Cars wrapped around in a circular, no figure eight, no infinity-shaped line whose end I could not identify. There were no visible staff, no visible signs anywhere. I paused and then watched two other cars drive up a road ahead of me and turn right into one of the lots. I followed.

We sat in the car for ten minutes. Fifteen minutes. I got out of the car for a minute to stretch my back and peered out across the pavement towards a tiny tent where I noticed some movement. Maybe they were getting ready to begin. Just as I got back in the car, a man behind me in a large truck honked at me. I wasn’t sure why, so I ignored it, but then suddenly he was beside my window, his face furious, his demeanor ready to explode—a fuse that had long been waiting for a light.

I lowered the glass and he barked at me: “The line is way back there! Do you want to get a ticket or something?” His words meshed with my pain and hardly made sense. I looked around to gauge where he might be pointing and I still could not deduce where the cars were entering, where they were wrapping around, where I should have gone, where I should now go. There were hundreds of cars. Several cars had pulled in behind me, equally as confused as to where the correct line began. My head began to pound as the pain and my exhaustion, as the medication I was on and my apprehension at being in the wrong wrapped around my brain cells, shrinking my thoughts to the singularity of complete and utter inaction. I froze.

I am a pretty hard-core rule-follower. Yup, exciting indeed. I like it when rules are followed by myself and others. Things make more sense. I know what to expect. It feels slightly safer in this wild world. I sat there in my frozen pain and frozen confusion and frozen shame that I might be in the wrong place because, god forbid, I am not one to cut lines.

My son’s quiet, yet concerned, muttering in the backseat shook me out of my inertia enough that I started to consider how I could pull out of where I was currently parked and move to where the man had angrily gestured. Just as I began to put my car in reverse, I heard a truck engine gun and tires screech and suddenly the man had swerved his truck in beside and slightly in front of me, blocking me from moving forward. Another car followed his lead and I was completely penned in. Fuming, he then climbed out of his truck and returned to me car side: “We were all here early, waiting!” he barked. “You are late! Go and get in line!” His fury terrified me. He began to walk away and then turned dramatically to deliver one final line, spitting it at me as his eyes narrowed, as he pointed and moved more threateningly close to me: “You are not special!”

No, no I am not. I have long tried so hard to let the world know this. I don’t know why anorexia afflicts other people, but when I struggled with it in my teens and then again in my twenties, here was the question I was posing: how do I disappear this being I am stuck in while still being in the world? Here’s the thing: I don’t want to be invisible. I just don’t want to be unitary. It feels such a broken way to exist, such an impoverished way to experience, such a bland, dull way to think.

Do you feel whole? Or do you feel wholly estranged from yourself, whatever that might be? Is that your paradox? I don’t want you to tell me your story so I can reform it. I don’t presume, as hooks implies of embracing while smothering an other, that “I can talk about you better than you can speak about yourself. No need to hear your voice. Only tell me about your pain. I want to know your story. And then I will tell it back to you in a new way. Tell it back to you in such a way that it has become mine, my own. Re-writing you I write myself anew. I am still author, authority.” I don’t want to author your life. I don’t even want to author my own. I want to know who you believe you are, who you think this “us” is? Doesn’t it hurt to be so hard? Don’t you feel stiff when walking and exquisitely fragile when you fall? So much hardness, so much broken glass. Where can you land, o singular one? I want to break out of this me so I don’t have to fall so hard and so far. I want to wander apart into wholeness. It is a fatal journey, but one worth taking.

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Siduri—the wise woman who counsels Gilgamesh to accept the inevitable mortality of being human—asks him, “Gilgamesh, why do you wander? The life that you seek you will never find.” We are all trying to make “it,” but what we make is each other—badly, often cruelly, but sometimes generously, sometimes lovingly. Does subjectivity require you to be a subject? Whose subject?

Writing did not used to be about authoring. It used to be a sacred activity, believed to be imbued with divine intention and transcendent opportunity. Writing held the same wonder and danger as speaking the name of a magical entity—the conjuring of this being into our human world. In the 2nd millennium BC, members of the Shang dynasty wrote questions to an oracle on pieces of bone. The bone was then burned and the patterns created as the bone cracked revealed the answers. If writing could channel something magical, something supernatural, then reading was also a portal. It still is. A portal to other places, other times, other beliefs, other ways of being, other minds. Do you still want to remain just a “you,” a degraded fragment as only a single human can be? "A hurtful act is the transference to others of the degradation which we bear in ourselves," wrote the wise Simone Weil. We are all degraded. The problem is trying to bear that alone in some seemingly heroic, but devastatingly doomed effort.

So, I invite you. Come looking for me. You won’t find me. I can’t even find myself. I wouldn’t know where to start and those who preoccupy themselves with that effort are like cats chasing their own tails endlessly. I’d rather not spend the rest of my life peering up my own asshole. I am not asking you to give up your guns or your pickleball, your maniacally long workdays or your special reading time with your kids. As Freud pointed out in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, we are expending extraordinary efforts in life to avoid pain. Early on in life, our protective barriers are tenuous, almost nonexistent, and in this state, experiences are more fluid and much more intense. But these “less restricted” experiences are overwhelmed by our immature psyches. But you, you have a more developed psyche. Maybe, in restricting what touches our psyches less, we could loosen our grip on me and let the breaches through. Crack open your “me” and you might find a “we” was there all along.